Restoration and Renewal: The Path to Recovery After Devastation

Published: 02 September 2024

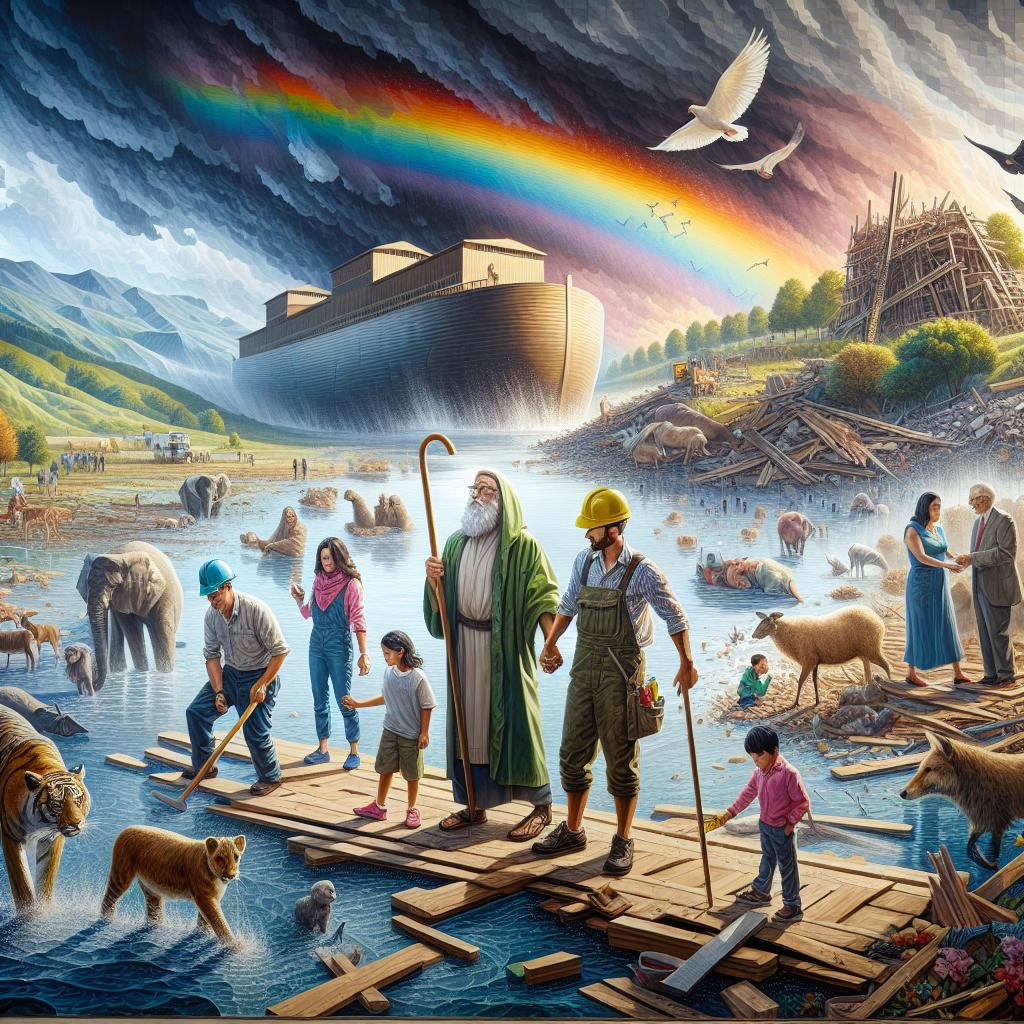

After Devastation... The Recovery

An amazing bounce-back after a catastrophe gives us insights into how the world recovered from the Flood.

When Mount St. Helens erupted on May 18, 1980, it caused widespread devastation in the surrounding area. The eruption transformed a once pristine forest, clear mountain streams, and tranquil lakes into a desolate wasteland covered in ash. Initial predictions suggested that the area would never recover and that it would be impossible for life to return. However, scientists soon discovered that these pessimistic forecasts were largely unfounded.

Within just three years, 90% of the original plant species were found to be growing within the blast zone. This remarkable resilience of the natural world had been greatly underestimated. While many species were completely eliminated from the blast zone, others survived and even thrived through various means.

The eruption of Mount St. Helens was unique in that it initially exploded sideways, spewing a ground-hugging steam blast filled with rocks outward from the volcano. This blast flattened over 200 square miles of forest in less than ten minutes. The extent of biological destruction was staggering, with countless organisms losing their lives. Despite this, some species managed to survive.

Ants, for example, survived in underground colonies, while salamanders found refuge in the soft wood of decomposing logs. Fish managed to survive in ice-covered lakes, and plant roots were protected by soil and snowpack. These unexpected survivors played a crucial role in accelerating the recovery process.

The recovery of the devastated area relied heavily on migration from beyond the blast zone. Birds and animals gradually returned to the landscape as they moved in from unaffected areas. Elk, being highly mobile, were able to enter and exit the blast zone at will, and their dung contained seeds and nutrients that helped accelerate plant recovery.

Beavers from adjacent forests followed water courses upstream to blast zone lakes. Even salmon and trout successfully ascended muddy and ash-clogged waterways in their instinctive urge to spawn. These examples demonstrate how various species were able to repopulate the devastated landscape by migrating from outside.

The recovery process at Mount St. Helens also challenged ecologists' theories of ecological succession. Typically, ecological succession involves the gradual replacement of pioneer species by climax species. However, at Mount St. Helens, both pioneer and climax species were found growing side-by-side, forcing ecologists to rethink their understanding of this process.

The recovery of Mount St. Helens provides insights into the return of life after Noah's Flood. Both events involved cataclysmic geological events, extreme volcanism, flooding, and the destruction of life on a massive scale. In both cases, organisms managed to survive and repopulate the post-disturbance landscape.

Just as many species were wiped out from the blast zone at Mount St. Helens, everything on dry land that had the breath of life in its nostrils perished during the Flood. The only survivors were those on board Noah's Ark. Similar to the migration of species to the devastated landscape at Mount St. Helens, animals would have gradually migrated from the landing place of the Ark, multiplying and repopulating the earth.

Birds likely played a significant role in the dispersal into the post-Flood landscape due to their capacity for flight. This may explain why flightless birds like New Zealand's Moa were able to survive in large numbers until hunters eventually arrived in the area.

The presence of "generalist" species, which can tolerate a wide range of environmental conditions and feed on various foods, was also observed during the recovery of Mount St. Helens. These adaptable species were among the first to colonize the devastated landscape. In Noah's time, it was the raven that left the Ark first, weeks before the dove was able to survive in the post-Flood world.

Additionally, many organisms managed to survive within the blast zone of Mount St. Helens, either as seeds, spores, eggs, or larvae. This suggests that species not taken on board the Ark could indeed survive cataclysmic events. The presence of billions of insects in the air column and their ability to survive in floating logs and debris further supports this idea.

The recovery of Spirit Lake, which was heavily impacted by the eruption, provides additional insights into the restoration of ecosystems after catastrophic events. Despite initial predictions that it would take 10-20 years for the lake to return to its pre-eruption state, it actually recovered in just five years.

The transformation of Spirit Lake was facilitated by the proliferation of bacteria in its warm and muddy waters. These bacteria played a crucial role in decomposing organic debris and clearing the lake of toxic chemicals. The influx of fresh water during winter rains and increased oxygen levels further aided the recovery process.

The remarkable recovery of Mount St. Helens and Spirit Lake highlights the extreme resilience of creation. It challenges skeptics who argue that recovery from a global catastrophe like the Flood would be impossible within a short biblical time-frame. Just as Mount St. Helens rapidly recovered, it is reasonable to believe that the regreening and repopulation of the earth after Noah's Flood could have occurred within a relatively short time.

Why This Matters:

The recovery of Mount St. Helens and Spirit Lake provides evidence that life can bounce back quickly after a devastating event. This challenges the notion that long periods of time are required for ecosystems to recover from catastrophes like Noah's Flood. The resilience observed in nature supports the biblical account of a young earth and a rapid restoration of life after global destruction.

Think About It:

- How does the rapid recovery observed at Mount St. Helens challenge conventional views on ecological succession?

- What implications does the resilience of creation have for our understanding of the biblical account of Noah's Flood?

- How does the recovery of Spirit Lake demonstrate the role of bacteria in ecosystem restoration?

- Consider the role of migration in the repopulation of devastated areas. What does this tell us about the potential for life to recover after a global catastrophe?